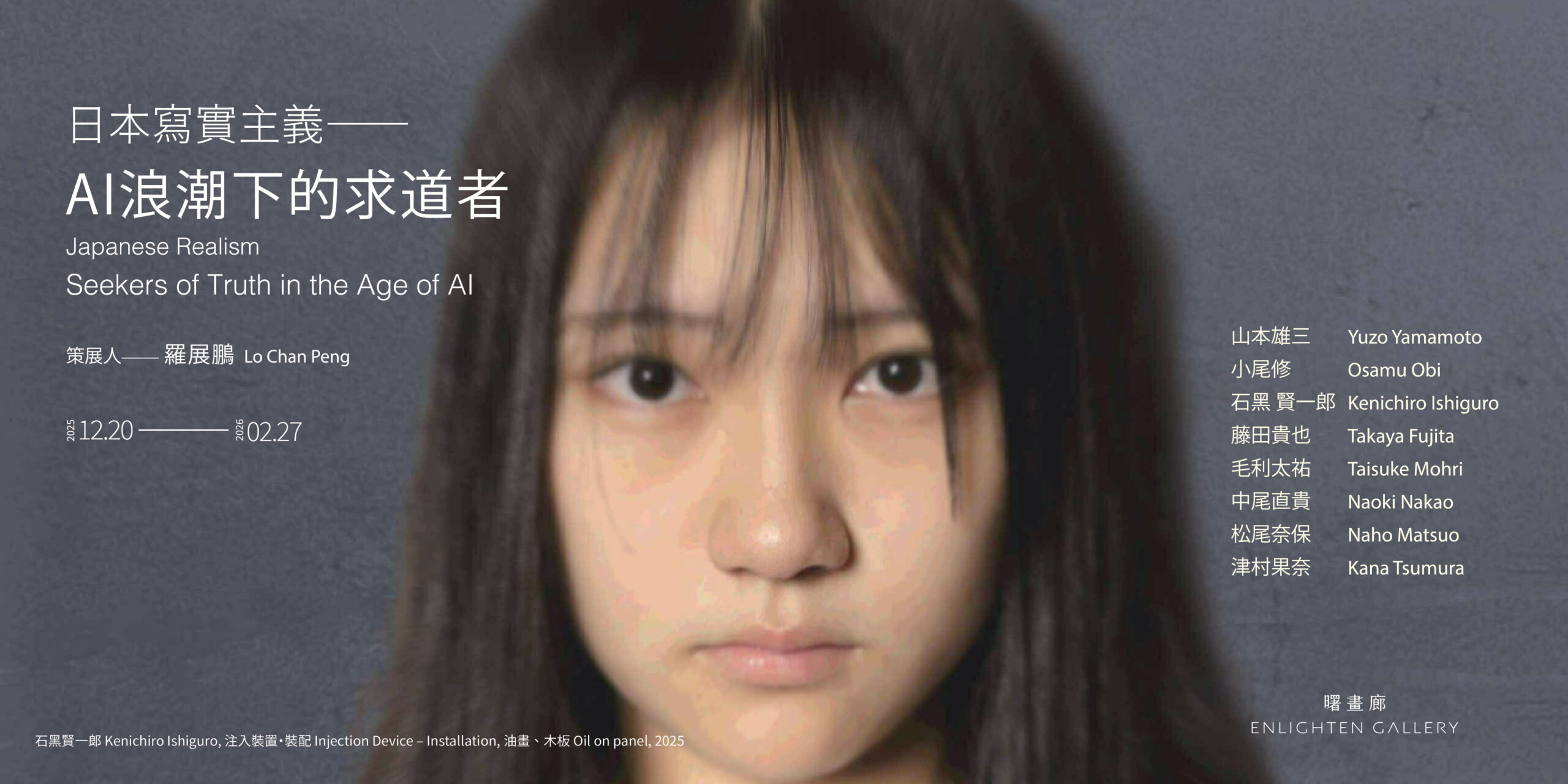

13 Dec Japanese Realism—Seekers of Truth in the Age of AI

Curator / Essay by Lo Chan Peng

In October 2022, humanity faced an unprecedented shock—the emergence of ChatGPT. Its arrival felt like a sudden awakening, as if the futures long foretold in films, novels, and manga had quietly become reality before we were prepared. Even before the advent of the text-generating AI ChatGPT, image-generating systems such as Midjourney had already been developing for some time. Soon after, similar platforms like Leonardo.ai and Stable Diffusion appeared, while major technology companies such as Google and Adobe began racing to develop new AI models. Unlike previous technological novelties—whether the illusory concept of the metaverse or blockchain technologies too abstract to explain to one’s parents—this wave of innovation introduced something immediately productive: creation itself.

Today, Midjourney is actively used by companies and individuals alike to generate tangible economic value, from fashion campaign imagery and graphic design to photography, comics, storyboards, and fine art. These outputs are not speculative fantasies but creations fully embedded in contemporary social and economic systems, capable of being directly transformed into value.

As throughout human history, the arrival of a new era often replaces or disrupts existing production chains. After the Industrial Revolution, countless laborers were displaced; similarly, today we may ask whether human models are still necessary for fashion campaigns. With AI-generated imagery, it has become entirely feasible to create a flawless model wearing a specified garment, posed under perfect lighting with an ideal expression. This reality forces us to confront an uncomfortable question. The same question emerges within the realm of figurative painting: as image-makers, do we still have a place? I confess that I have asked myself this countless times in the quiet hours of the night.

What, then, is most terrifying for creators when facing AI?

The greatest fear is this: unless we completely disconnect from the internet and never upload our work again, the moment we share our creations online, we inevitably become part of AI itself.

The world will always need art—but will it still need artists?

Carrying this anxiety, I traveled to Tokyo in early 2023 for an exhibition, continuing my long-held habit of visiting artists’ studios. I know well that one can never truly understand an artist through a single artwork; each piece is a condensation of a fleeting moment in that artist’s life, a transient point in time. Just as we cannot fully understand a person after only a few meetings, artworks alone remain partial. Yet through visiting studios, I can come closer to understanding the artist and their work, touching upon a form of humanity that cold data can never simulate.

With the generous assistance of artist Yuzo Yamamoto, I was able to visit the studios of many Japanese artists—an extraordinary experience not only for art lovers, but for myself as well. Artists rarely welcome interruptions to their working days; perhaps my being from Taiwan, or my identity as a fellow artist, afforded me special hospitality. Regardless, I visited many studios during this journey. Each visit felt akin to stepping into a great museum, where crossing the threshold reveals an invisible boundary. Inside each studio, the air itself felt different. Each artist breathes their own unique atmosphere, having shaped their space into an extension of themselves. For realists, through long years of craftsmanship, life itself is poured into the studio.

Craft and Technique: The Absolute Difference from AI

When discussing realism, we inevitably return to the original meaning of the word: “real.” Historically, “real” did not mean photographic accuracy—many works were already highly realistic—but rather a shift in perspective, from the idealized beauty favored by aristocracy toward the lived realities of the middle and lower classes: newspaper boys, elderly women, and scenes of everyday life.

Returning to the present, contemporary realism is often understood as highly technical figurative painting. This does not mean a simple reproduction of reality; modern realism may incorporate digital imagery or elements of fantasy. What defines it instead is an extraordinary level of technical mastery—a craftsmanship rooted in the heart and expressed through the fingertips.

Oil painting, since Jan van Eyck in the late 14th century, has evolved over more than five centuries into an immense technical system, encompassing countless oil recipes, ground preparations, and pigments—processes akin to alchemy. Some artists become such experts in materials that painting itself becomes secondary. This is what I mean by “high technicality.” Among the Japanese realists I visited, each has found a distinct position within this vast system and developed a unique personal language. One might even say that they have “Japanized” realism.

Much like how Japanese craftsmanship transformed American denim into a globally revered product, Japanese realism has evolved beyond its Western origins. In a world where conceptual art has often moved away from technique since Duchamp, realism cannot exist without craftsmanship. Indeed, craftsmanship itself is inseparable from realism.

—

“Japanese Realism—Seekers of Truth in the Age of AI”

Curator|Lo Chan Peng

Artists|Yuzo Yamamoto、Osamu Obi、Kenichiro Ishiguro、Takaya Fujita、Taisuke Mohri、Naoki Nakao、Naho Matsuo、Kana Tsumura

Period|2025.12.20-2026.02.27

Opening|2025.12.20 15:00

Art Talk|2025.12.27 15:00

Venue|Enlighten Gallery (1F., No. 222, Shidong Rd., Shilin Dist., Taipei)